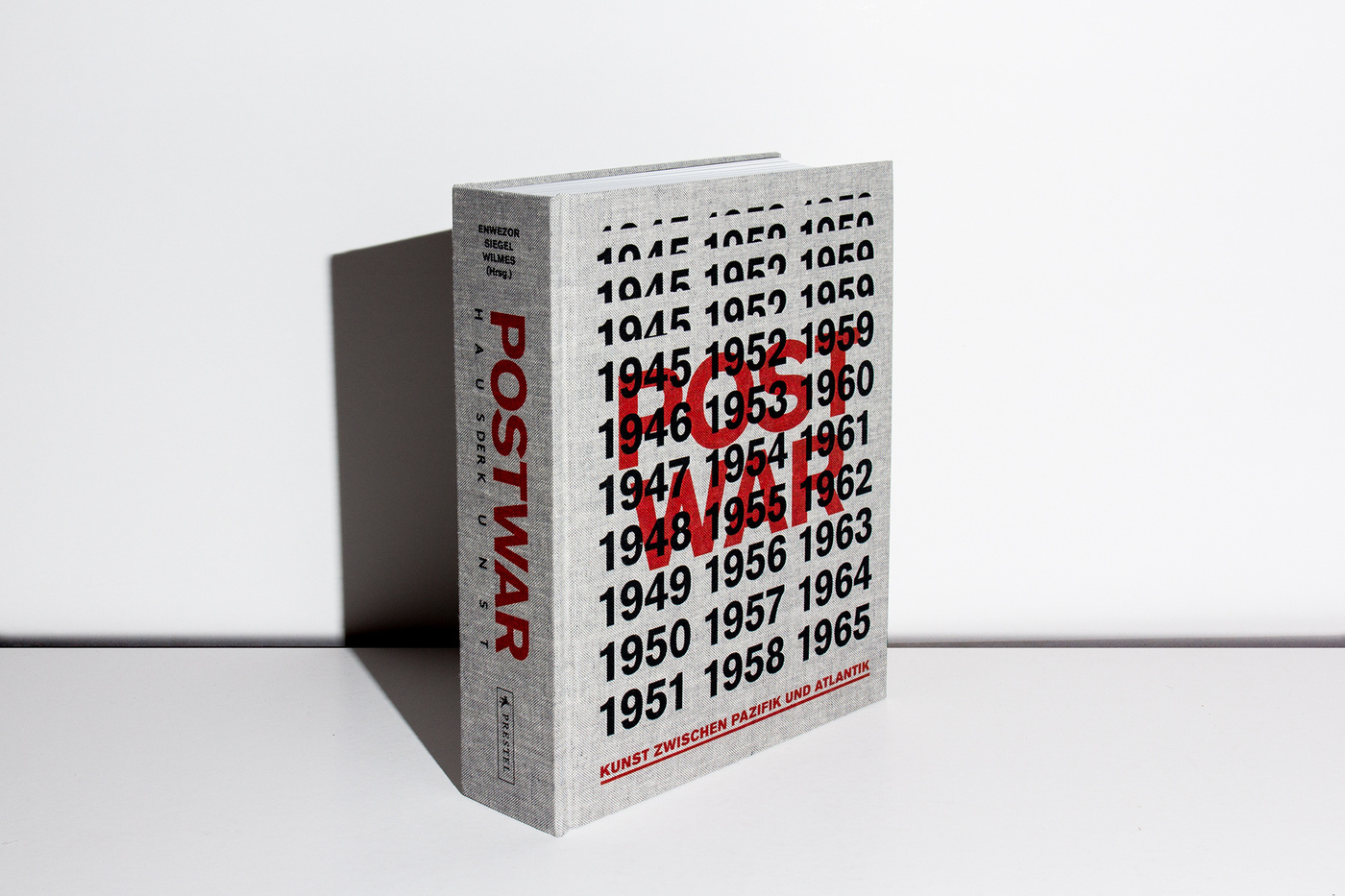

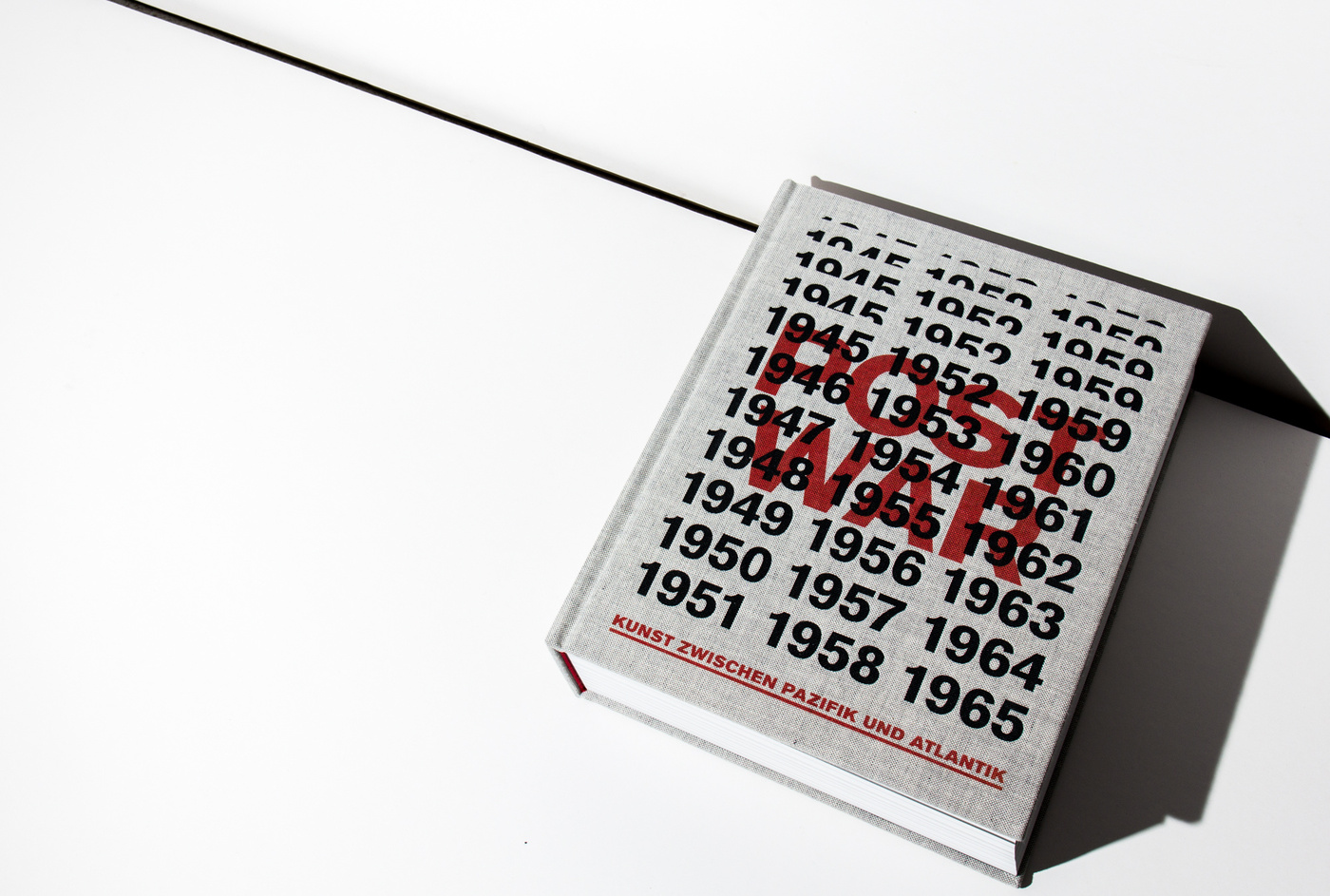

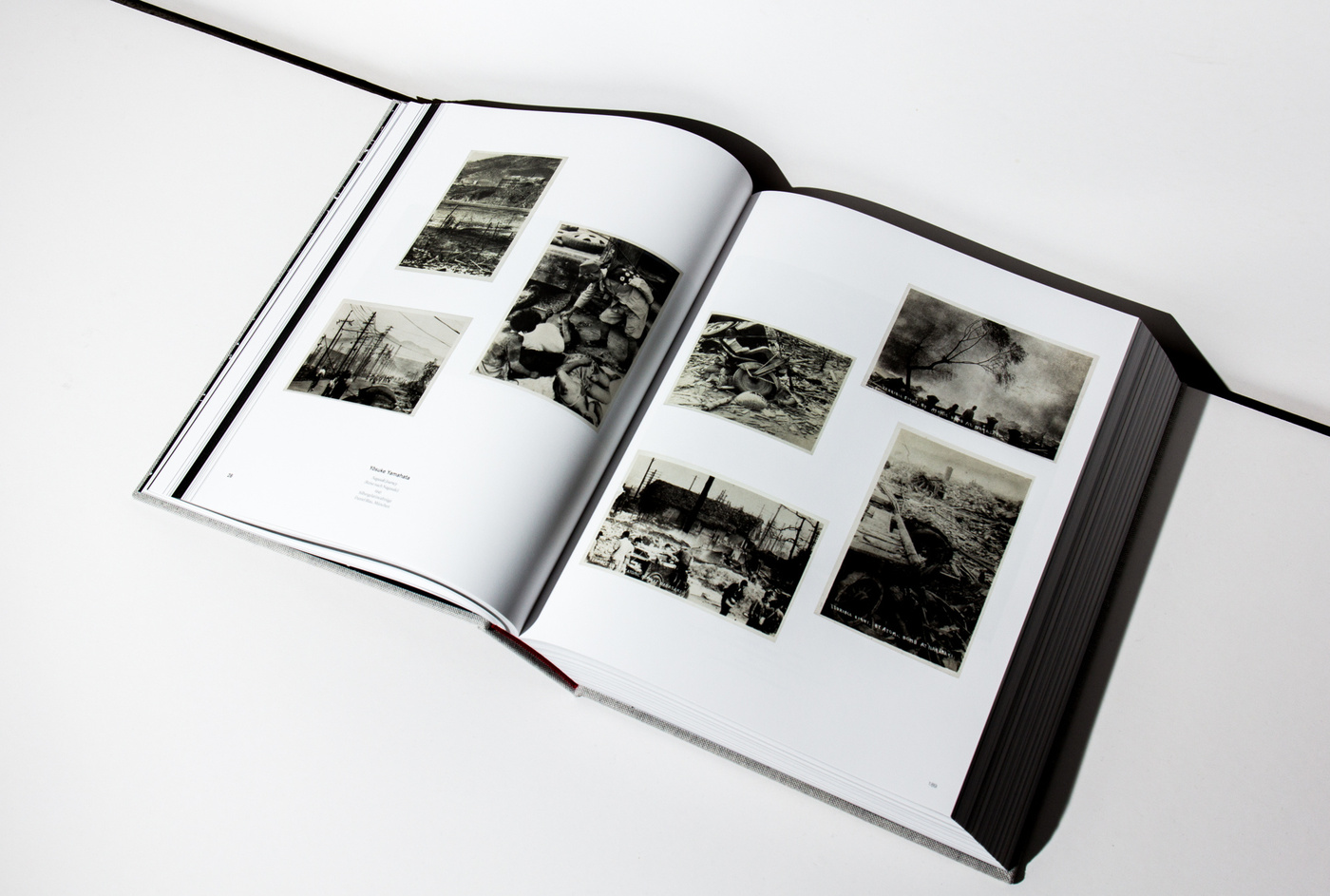

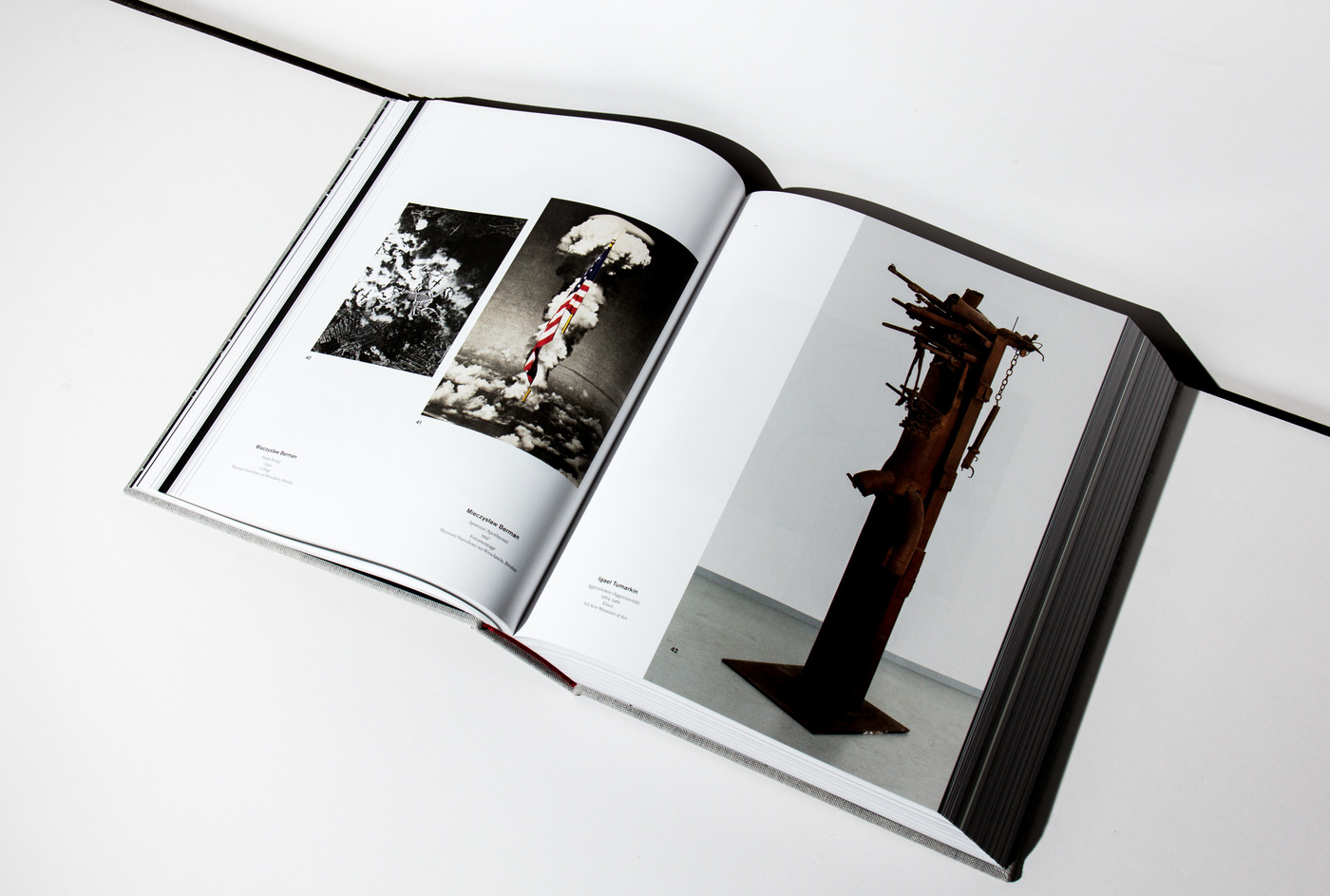

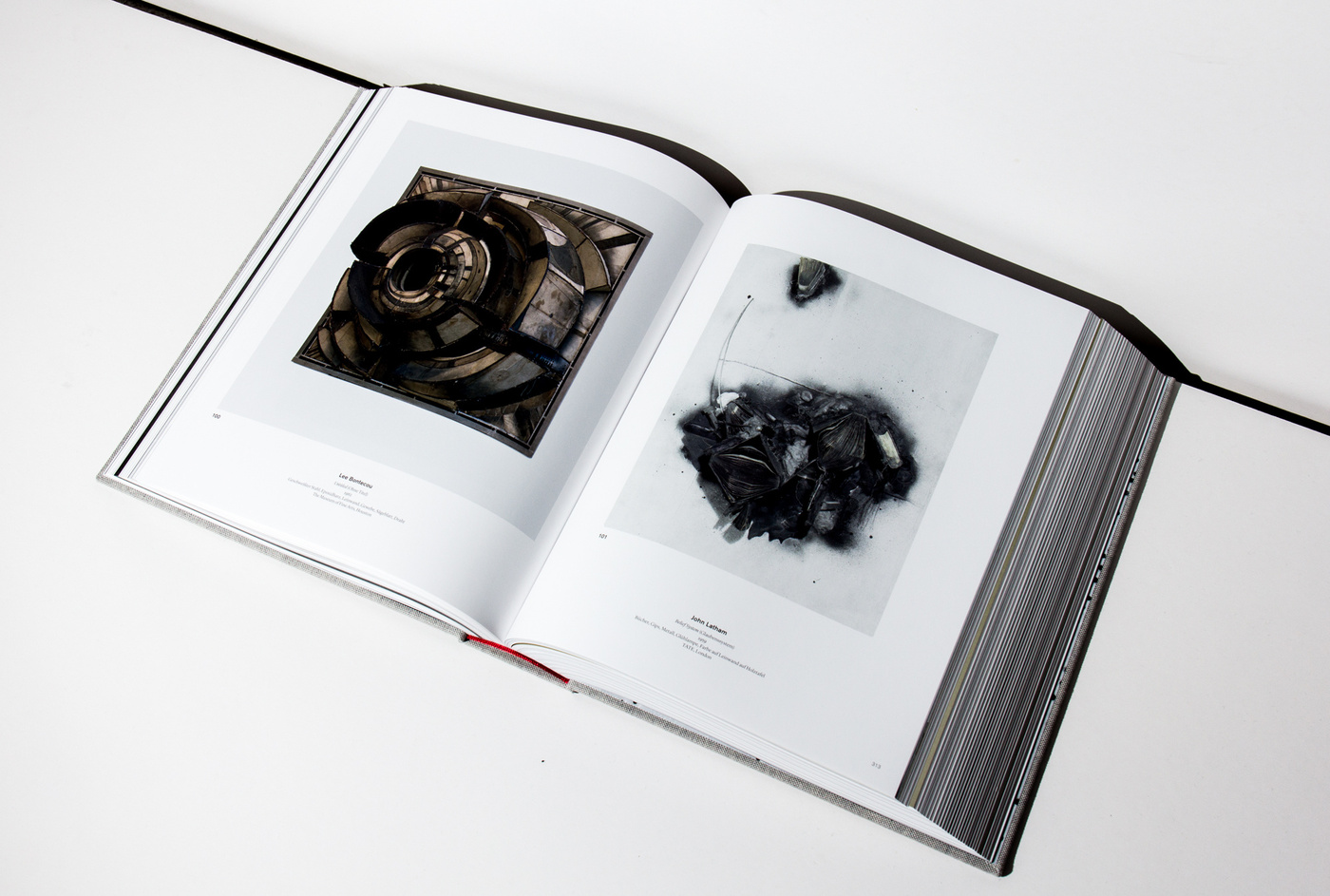

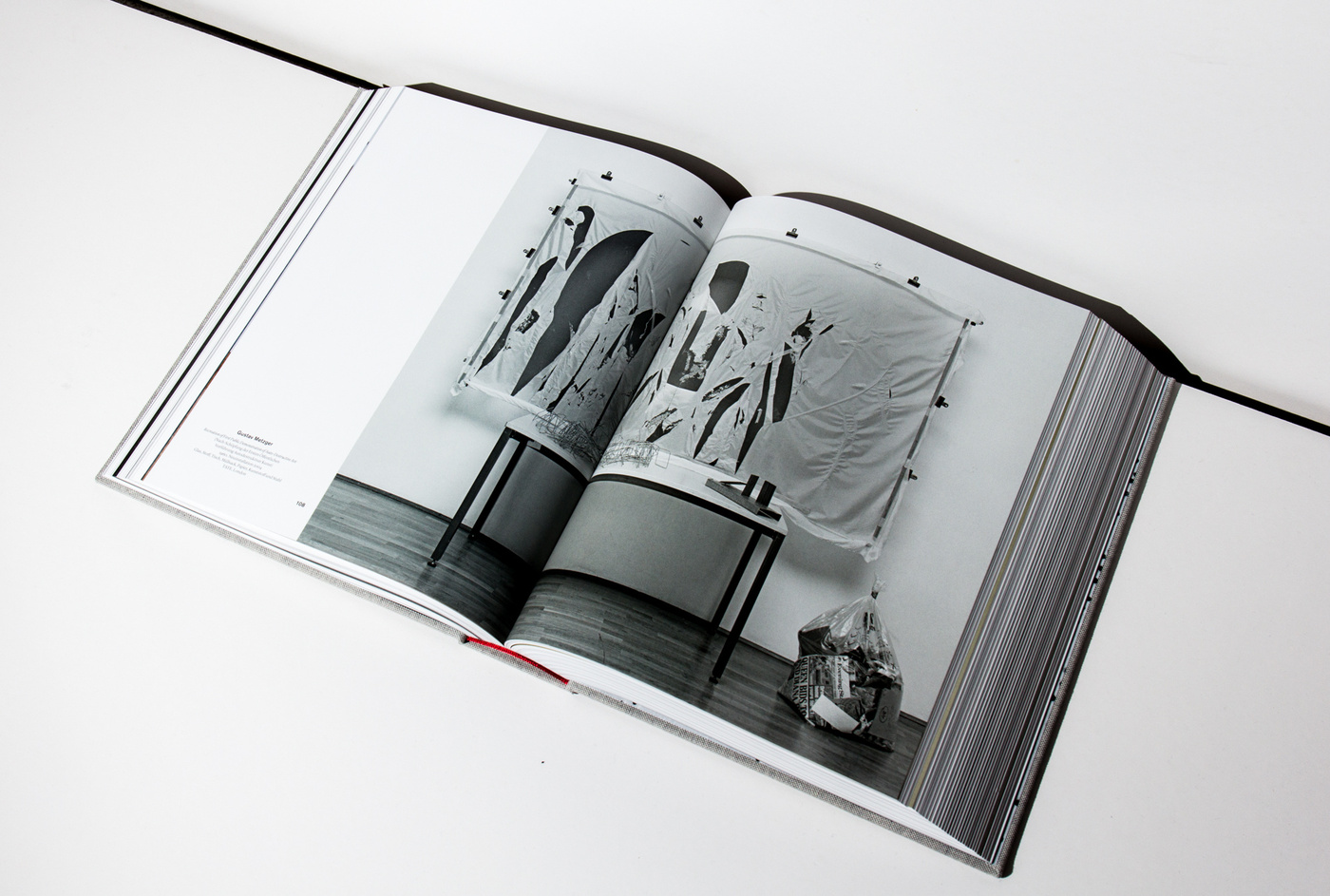

Worldwide – Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965

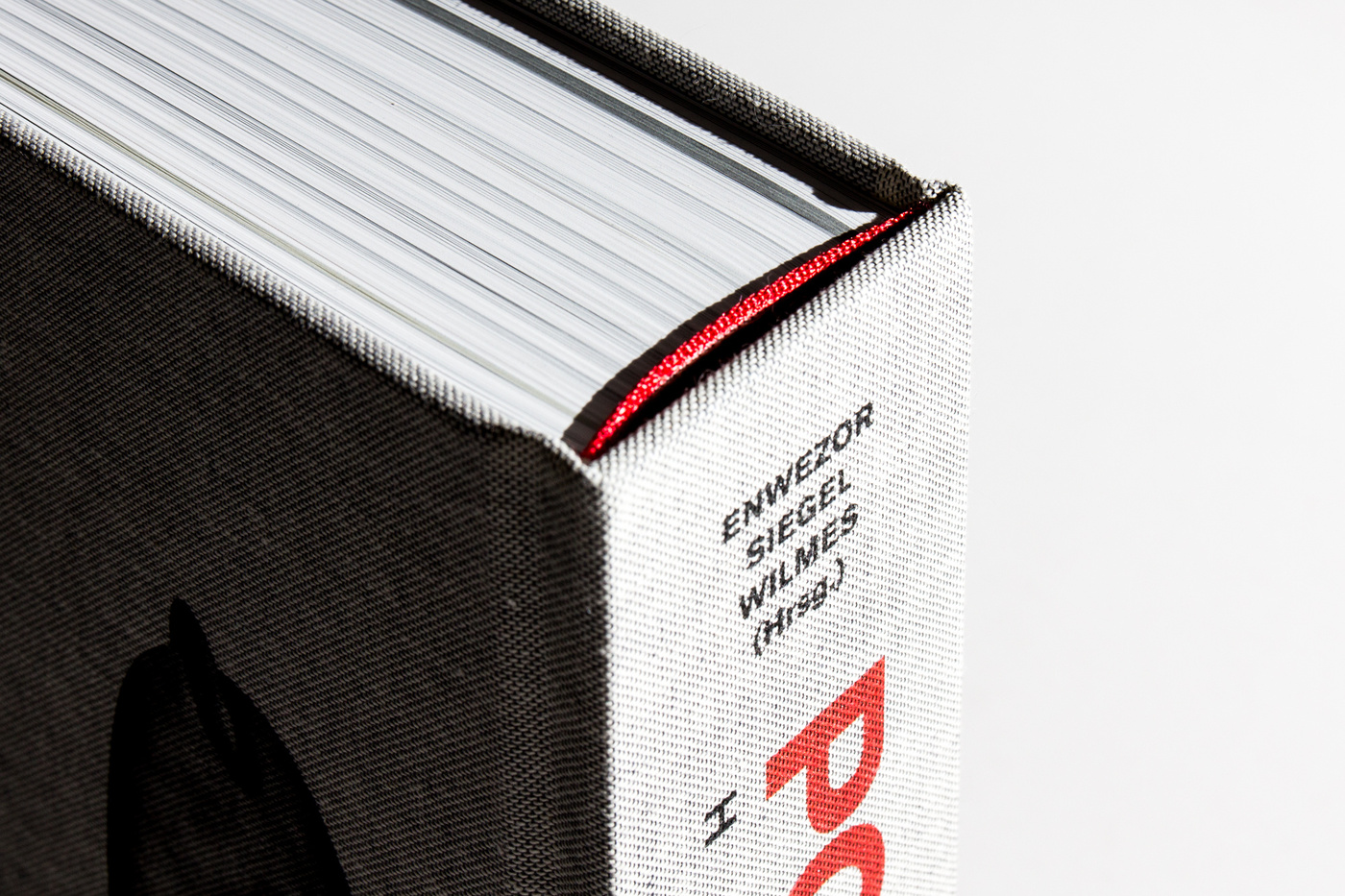

Haus Der Kunst MunichA massive endeavour that is what we could call it. Not only for the production of the PostWar book and short guide, but also for Okwui Enwezor and his staff at Haus der Kunst in Munich. It’s been a pleasure again to work with Okwui on his impressive view on the world and the connections he is able to draw between the single pieces and movements after WWII. But, we will let him speak now ... in the preface of the book, Okwui Enwezor is describing it all very precisely what was wrong, or not entirely right with all the postwar exhibitions and catalogues up until now ... in a very few words ... there was art everywhere after WWII, not only in the north western hemisphere....

Preface by Okwui Enwezor

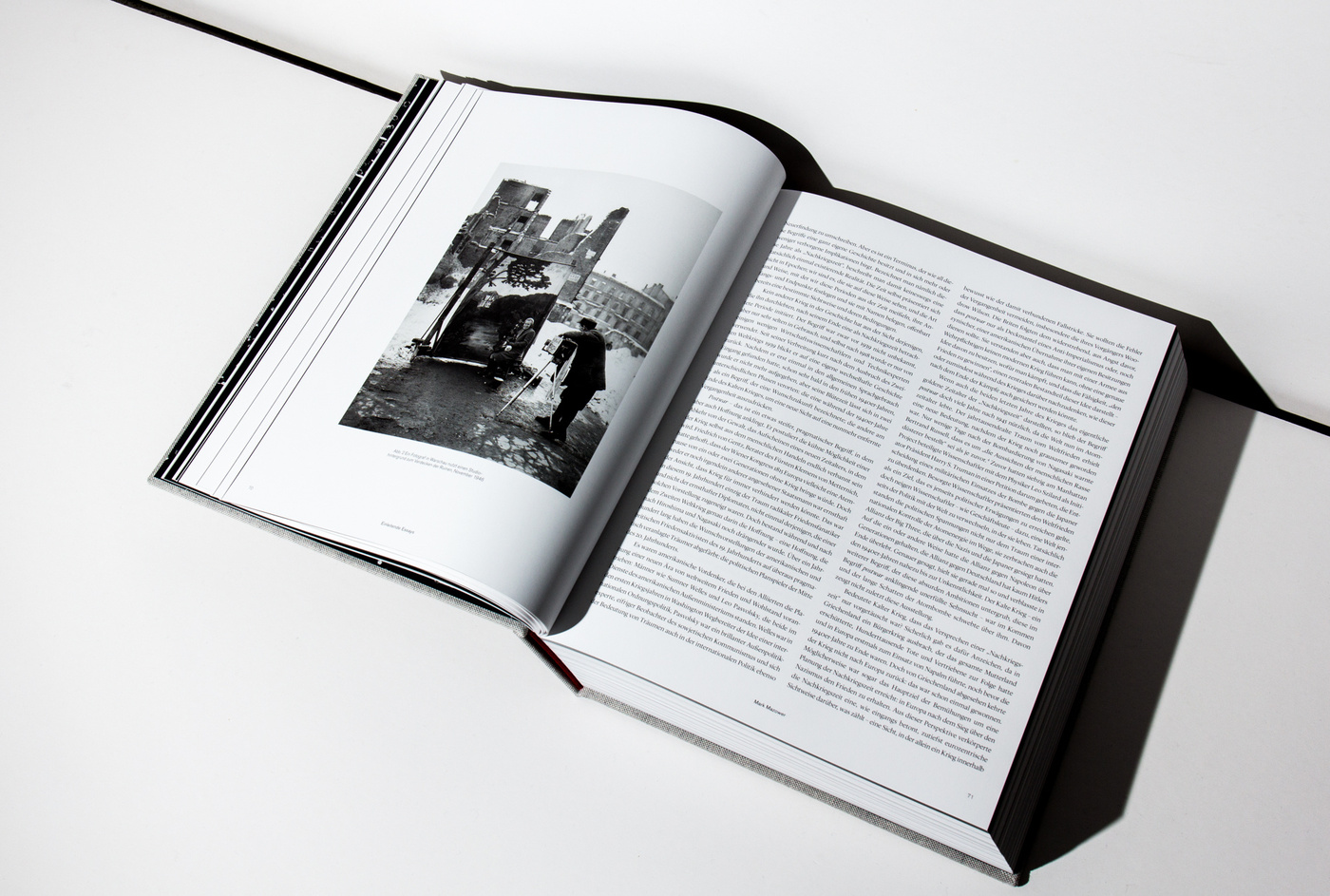

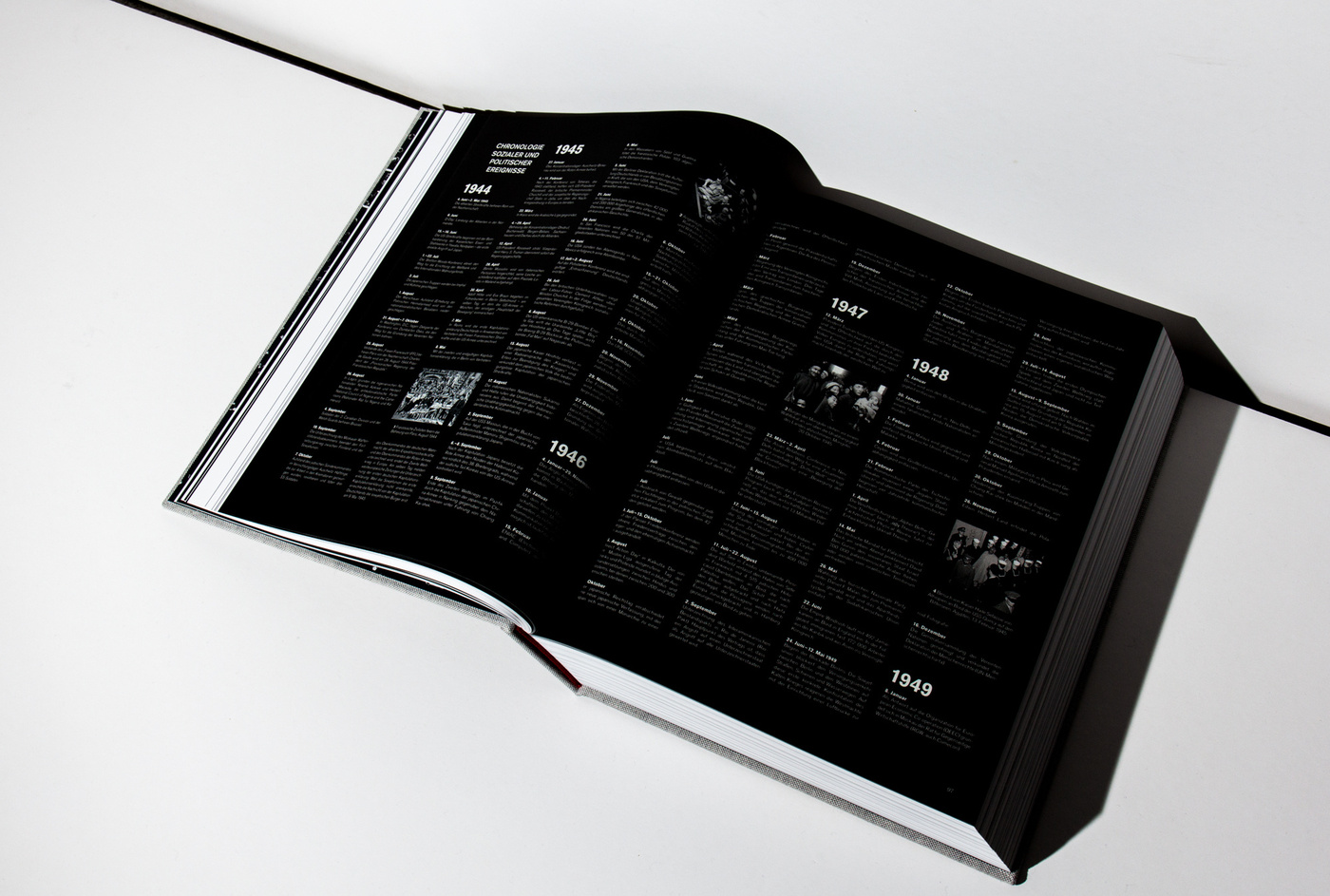

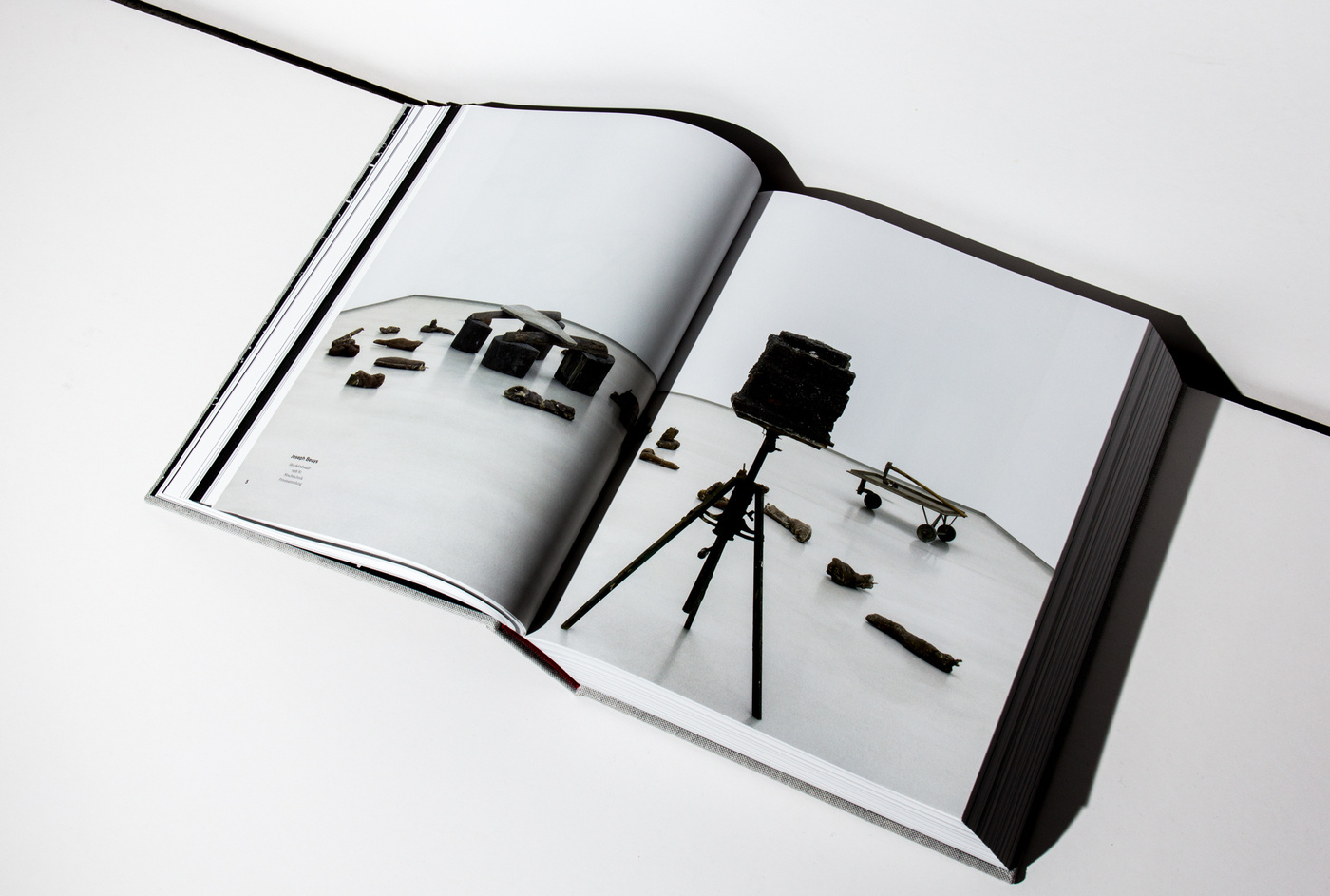

In his posthumously published Prison Notebooks, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, writing in the 1930s, in the depths of his incarceration by the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini, made the following observation: “The challenge of modernity is to live without illusions and without becoming disillusioned. I am a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.” Gramsci’s reflection on modernity is all the more captivating for having anticipated so succinctly the wretched spirit engendered by the catastrophe of World War II across the world. For many who survived the war—especially those who witnessed the concentration camps or the destruction wrought by the atom bombs, saw the images of destroyed lives and cities that these disasters produced, and lived through the social conditions of the period—to refuse to become disillusioned required extraordinary vigilance. Even before the war ended, the prescient incisiveness with which Gramsci had confronted the positivist idealism of modernity had united many modern artists, thinkers, policy-makers, legal theorists, and ordinary people around a singular fact: the necessity of emerging from the unprecedented trauma and violence of World War II without illusions, particularly at a time when humanity faced the daunting task of refusing disillusionment while building an entirely new modern and humanistic global compact. In Europe and Japan, the postwar period inspired a profound reflection on how to assimilate the lessons of the war and the invidious statecraft of colonialism, while also recognizing, without equivocation, the quest of the colonized for the end of colonial empires and imperial dominions. Both the victors and the vanquished of the war had to live up to new responsibilities, to which end they instituted new programs and policies to allow a smooth transition from a bellicose period to a more peaceful one. It is in this sense that within the remit of this project “postwar” should be seen not as purely an aftermath but as a horizon into which the ideals of global emancipation and decolonization could be projected as the new world order transitioned into a multilateral system of governance. In culture, similar ideals were pursued and questions were raised across the world around issues of art and heritage, scientific and educational exchange, cultural preservation and social interaction. These reflections were important contributors in the founding of UNESCO in Paris in 1945. From the defeat of Japan and Germany to the retreat of empire; from the creation of the Atlantic charter, the Pacific alliance, and the Warsaw pact to the building of a system of multilateral global institutions; from decolonization and the emergence of new nation states to the partition of others; from revolutions to dictatorships, Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 probes the creative ferment in which artists attempted to come to terms with the dawn of a new contemporary era. Through the vital relationship between artworks and artists, produced and understood from the point of view of local and specific contexts, Postwar aims to project a broad global understanding of the historical forces that attended the shaping of art after 1945. Covering the years 1945 to 1965, the exhibition proposes, through exhaustive research and case studies organized across regions, to explore the global view of contemporary art in the wake of the radical geopolitical transformation and realignment after the defeats of Japan and Germany. It is thus positioned not only as a reflection on the defeat of the aggressive regimes located on the shores of two oceans—the Pacific and the Atlantic—but also as a tracing of the spaces of art across the sweeping lines of those two oceans on five continents. By mapping these oceanic lines and their continental contours, Postwar straddles nations, political structures, economic systems, institutional frameworks, and ideological positions. More important, it engages with the vividness of the artistic systems and cultural networks of the period. Postwar can also be understood as the site of making and unmaking, connecting the ceaseless points of movement of the cosmopolitans and the diasporic, the exiles and the displaced, the immigrants and the refugees. From this turning point in global history it is possible to see the strong shift in artistic identities fomented by the entangled histories of the postwar period: who made art? Where and why, with what and how? The exhibition is devoted precisely to the untangling of this question. Employing a dramaturgical and social lens, Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 is centered in the interregnum between recovery from the devastation of the war and the creation of new artistic networks in the war’s aftermath. It responds to the multifarious conceptions of art among artists working with a vital awareness of a world created from conflict and within the experience of change. For these artists—who lived in different parts of the world, and many of whom were scarred by war and by imperialism, colonialism, racism, and segregation—the idea that art and artists had roles to play in such a period of instability, while constructing fresh insights into human culture and creativity, was fundamental to the shaping of a new artistic modernity. Artists were also deeply involved in the search for new subject matter, creating contemporary forms and harnessing materials in fresh ways that have since come to define modern and contemporary art. It should also be noted that the two decades covered here, from 1945 to 1965, marked a cultural turning point: the end of European dominance of contemporary around the world, the rise of the international prominence and hegemony of contemporary American art, popular culture, and mass media, and the incipient globalization of art. For even as the United States was consolidating its newly found cultural position, other nations, in South America, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and East and Central Europe, were busy as well, exploring and rethinking the artistic paradigms of their respective contexts. This changing of stakes in the language, material, and form of art led artists to develop new and alternative modernities to mirror the changed terms of geopolitical dialogue across the world. In Europe, as the Cold War divided the continent into two separate ideological spheres—the Warsaw Pact countries of Eastern and Central Europe, allied with the Soviet Union, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization countries of Western Europe, allied with the United States—the emerging global South of twenty-nine newly independent Asian and African countries convened in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955 to lay the foundation for the principle of nonalignment, of supporting neither East nor West but instead “facing forward,” in the memorable phrase of Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah. In the arts, even while the ideological fissure created by the competition for cultural dominance between East and West, communism and capitalism, socialism and liberal democracy, created a crude binary in the way the terms “abstraction” and “socialist realism” were taken as moral equivalents, artists in newly independent countries were discovering the role that they could play in nation-building and the advancement of a de-Westernized national culture. Artists across the world grappled not only with aesthetic and formal issues of artistic creation but also with debates on the correct ideological and cultural position: conformity or individualism, subjectivity or collectivity, regionalism or internationalism, alignment or nonalignment. In recent years, scholarship around the world has begun to shed light on the many alternative histories of contemporary art from this period, and these inquiries have created opportunities to interrogate former conclusions and the general history of the postwar period. They have often ended up challenging and expanding previous discourses of modernity that were grounded in Western practices of exclusion. We in turn have gained critical insight into the art of the postwar era by broadening the borders of art history since 1945 while reflecting back on the debates and discourses that were crucial and fundamental to artists and their ideas in different regions of the world. At the same time, we have explored how different terrains of artistic practice and conditions of production that flourished in previously underrecognized and understudied art-historical canons can enrich our current understanding of postwar art history. The emergent scholarship on postwar art has made a deep impact on the curatorial arguments that frame this exhibition; in turn, it requires exhibitions such as this one to foreground them. What is crucial is that it is the art itself, and the systematic conceptual and aesthetic approaches undertaken by the artists of the period, that have been the real revelation. It is our hope that some of these issues will come to sharper relief in the course of the exhibition. Postwar has involved 218 artists from more than sixty countries and 150 lenders from 36 countries. A project of this complexity, scope, and ambition must be multipronged in its affiliations and networks. After nearly five years of research, it gives me great pleasure to thank my two colleagues and co-curators of the exhibition—Ulrich Wilmes, chief curator and deputy director of Haus der Kunst, and Katy Siegel, Eugene V. and Claire E. Thaw Endowed Chair in Modern American Art at Stony Brook University, New York—for the incredible privilege of developing and realizing such an important exhibition with them. Ulrich’s and Katy’s exemplary knowledge of the field, their commitment to research and their marshaling of every available intellectual resource at their disposal, and finally their insistence on building a more global account of postwar art has meant that together we could curate an exhibition worthy of the ambition we all invested in its making. A project of this globe-spanning dimension requires not only delicate diplomacy but also a shared common horizon among participants and collaborators. To this end we are pleased to acknowledge the generous support provided to us by so many artists, colleagues, lenders, archivists, foundations, museums, artists’ estates, galleries, and research institutes over the course and the process of its planning. Our immense gratitude goes to the patron of this exhibition, the honorable Dr. Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany, whose support has been vital to the objectives of Haus der Kunst as an open, global institution. We wish to thank our principal collaborating institution, the Brooklyn Museum, New York, and especially Anne Pasternak, president and director; Nancy Spector, deputy director and chief curator; and Sharon Matt Atkins, vice director, exhibitions and collections management, for their enthusiastic endorsement of the exhibition and for making it possible to present it in New York, a city where an important body of postwar art was created and historicized. We are indebted to so many individuals and organizations who have played key roles in funding Postwar. We are particularly thankful to the shareholders and the major supporter of Haus der Kunst: The Free State of Bavaria, the Gesselschafft der Freunde Haus der Kunst, and the Alexander Tutsek-Stiftung for their annual funding support. As the planning of the exhibition began, we received two major grants from the Kulturstiftung des Bundes, Berlin, and the Goethe Institute, Munich, that underwrote the exhibition and research. These two grants were strengthened by two more from the Art Mentor Foundation, Lucerne, supporting the exhibition and our educational programs. We are very grateful to the boards and officers of these organizations, and especially to Hortensia Völckers, Artistic Director, and Alexander Farenholtz, Administrative Director, Kulturstiftung des Bundes, Berlin; Johannes Ebert, General Secretary, and Hans-Georg Knoop, former General Secretary, Goethe Institut, Munich; and Evelyn Kryst, Karin Ebling, and Miriam Lüthold Lindén, Art Mentor Foundation, Lucerne. Further thanks go to Darren Walker, President, and Elizabeth Alexander, Director, Creativity and Expression, at the Ford Foundation, New York; Wolfgang Heubisch, President, and Michael Barnick, Heinke Hagemann, Irmin Rodenstock-Beck, and Philippe Litzka, Members of the Board, of the Gessellschaft der Freunde Haus der Kunst; and Hans-Ewald Schneider and Ingrid Schuchlenz at Hassenkamp, Cologne, for the additional funding support they provided to us. Finally, the staff of Haus der Kunst and the core organizational team of this exhibition have played an impressive role in shaping its outcome on every level. It is with gratitude that I recognize their contributions and thank each of them for ably shepherding the entire process and bringing special professional care and sensitivity to the realization of this mammoth project.

Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965

EXHIBITION 14.10.16 – 26.03.17

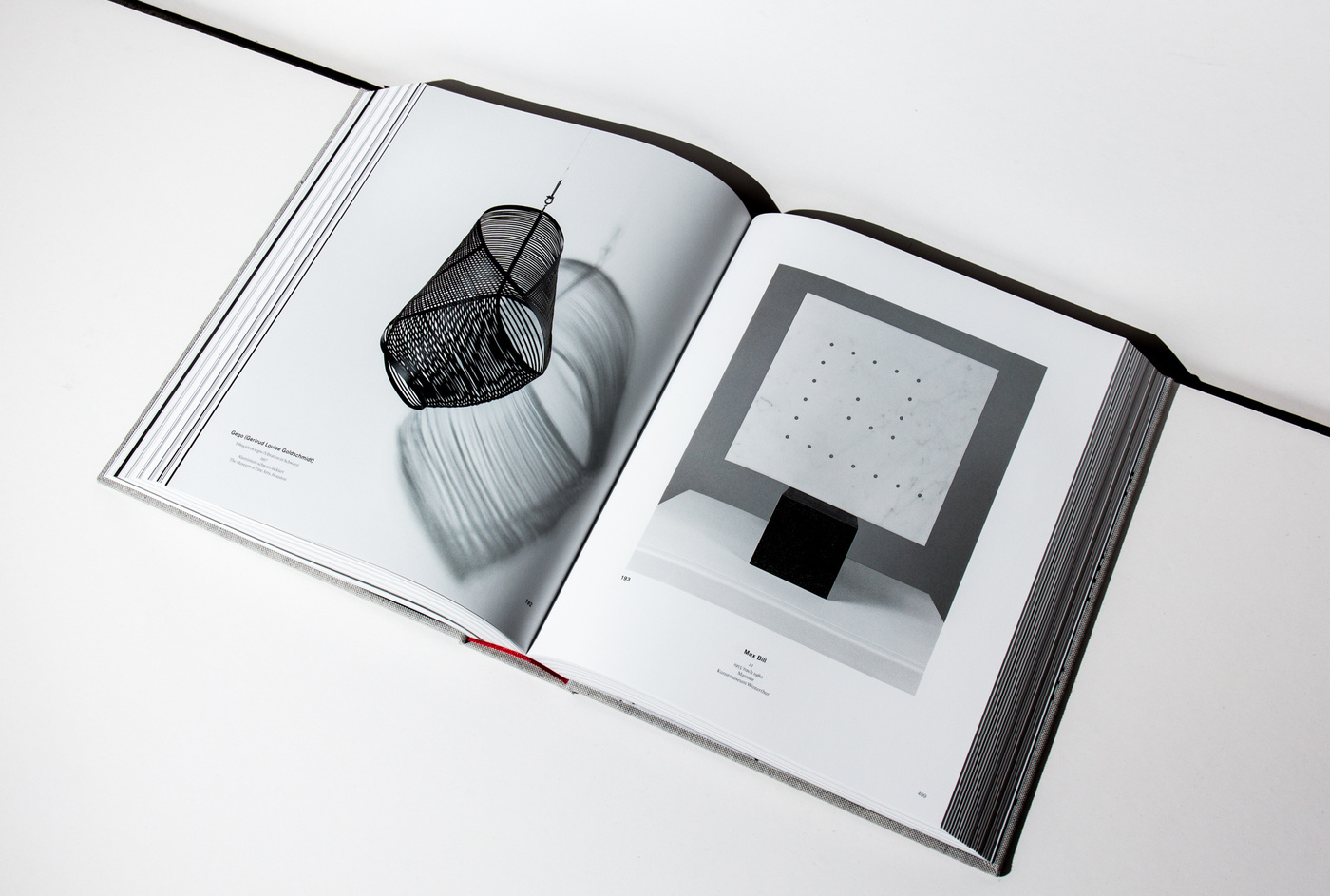

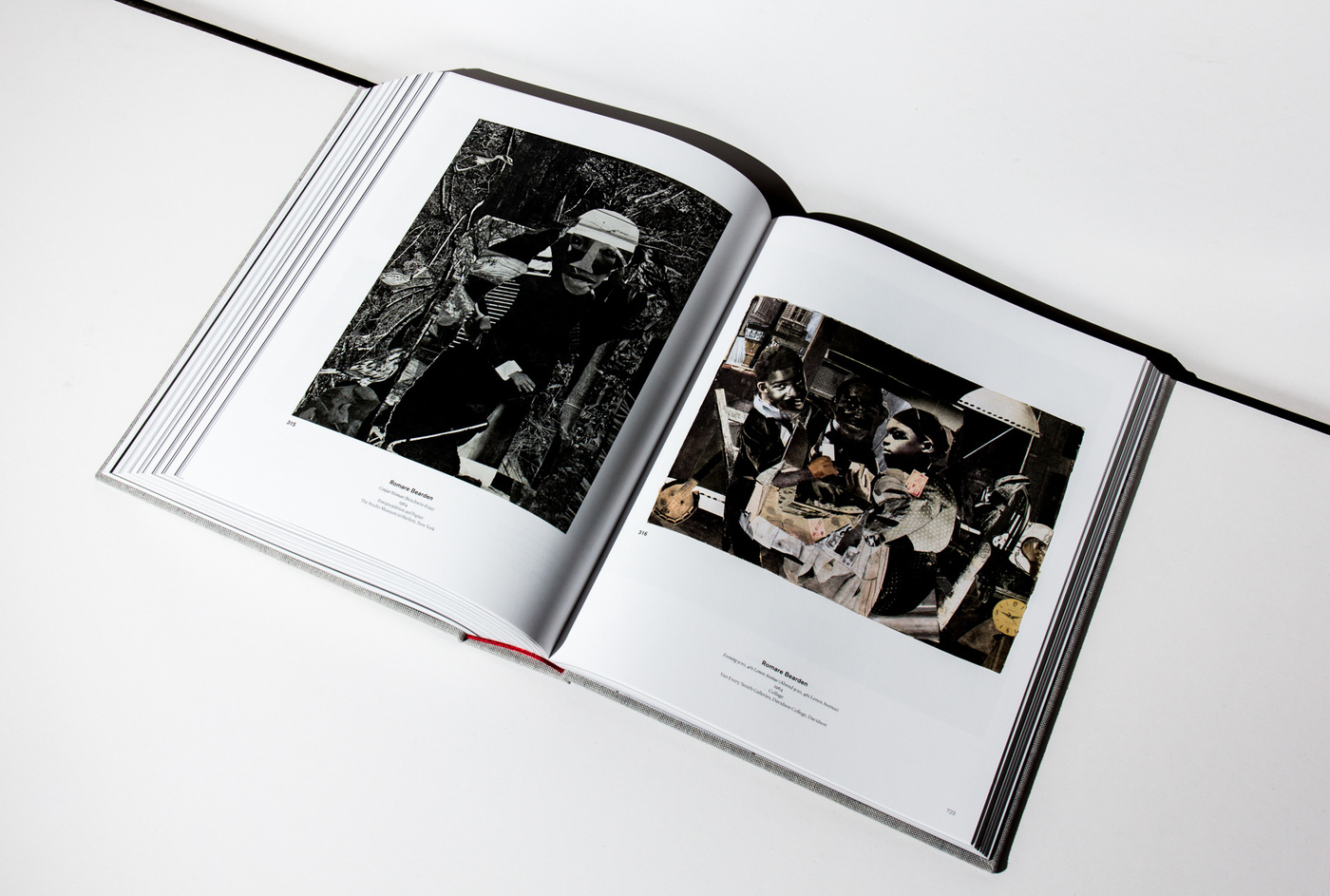

The exhibition examines the vibrant and turbulent postwar period as a global phenomenon for the first time in recent exhibition history. In eight dramatic chapters, the exhibition guides visitors through the first 20 years following the end of World War II, demonstrating how artists coped with and responded to the traumas of the Holocaust, the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; how the two political blocs of the Cold War exploited the arts and created competition between realism and abstraction, and how displacement and migration produced new cosmopolitan contexts across the world. The postwar period also marked the end of European colonial systems; the rise of nation-building, decolonization and liberation movements; the partition of countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East; as well as the civil rights movement in the United States. These changes unleashed an incredible energy visible in the art of the time. New technologies began to pour into everyday life; the space age fascinated artists as well as the masses, opening up a completely new and dynamic field of artistic consideration.

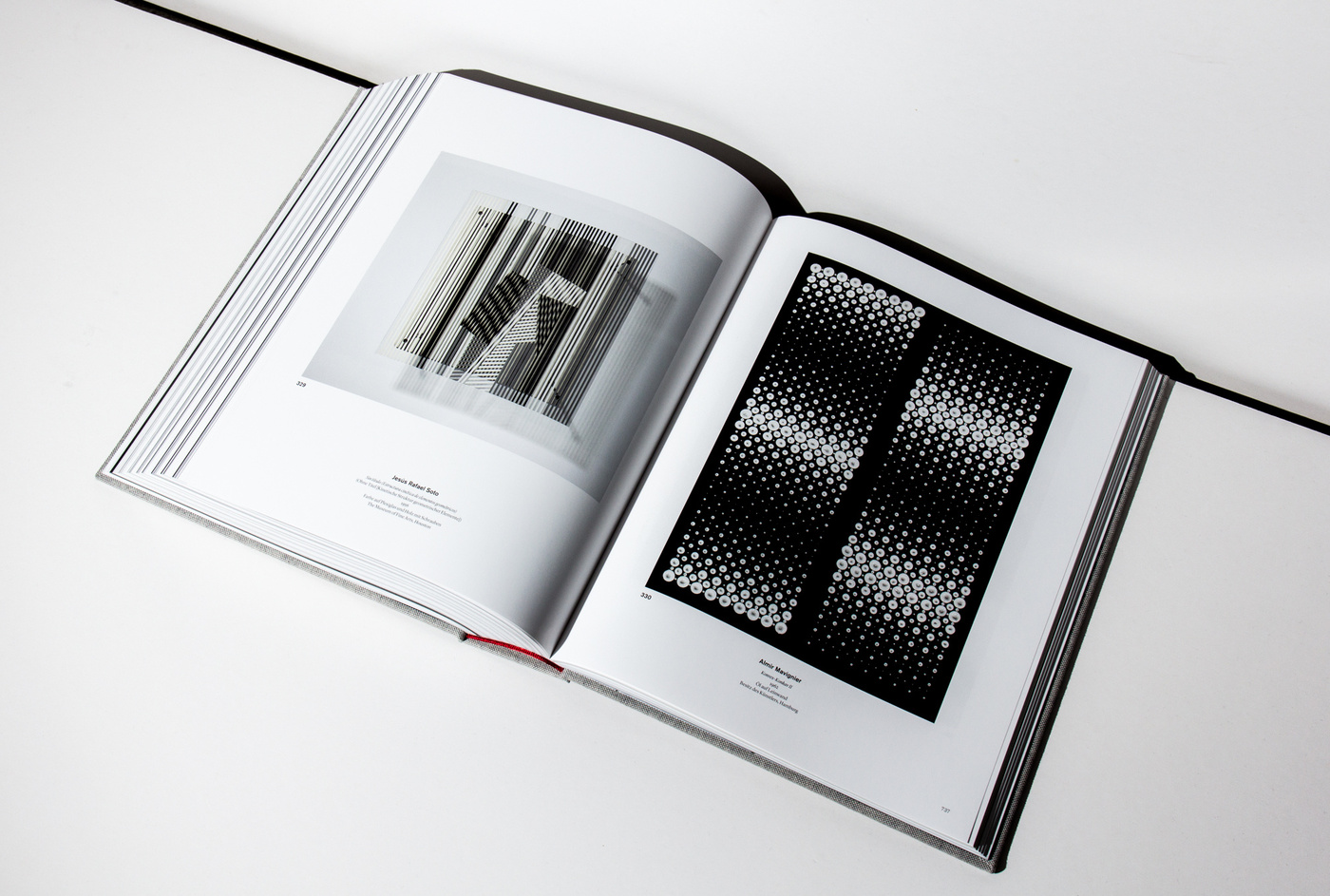

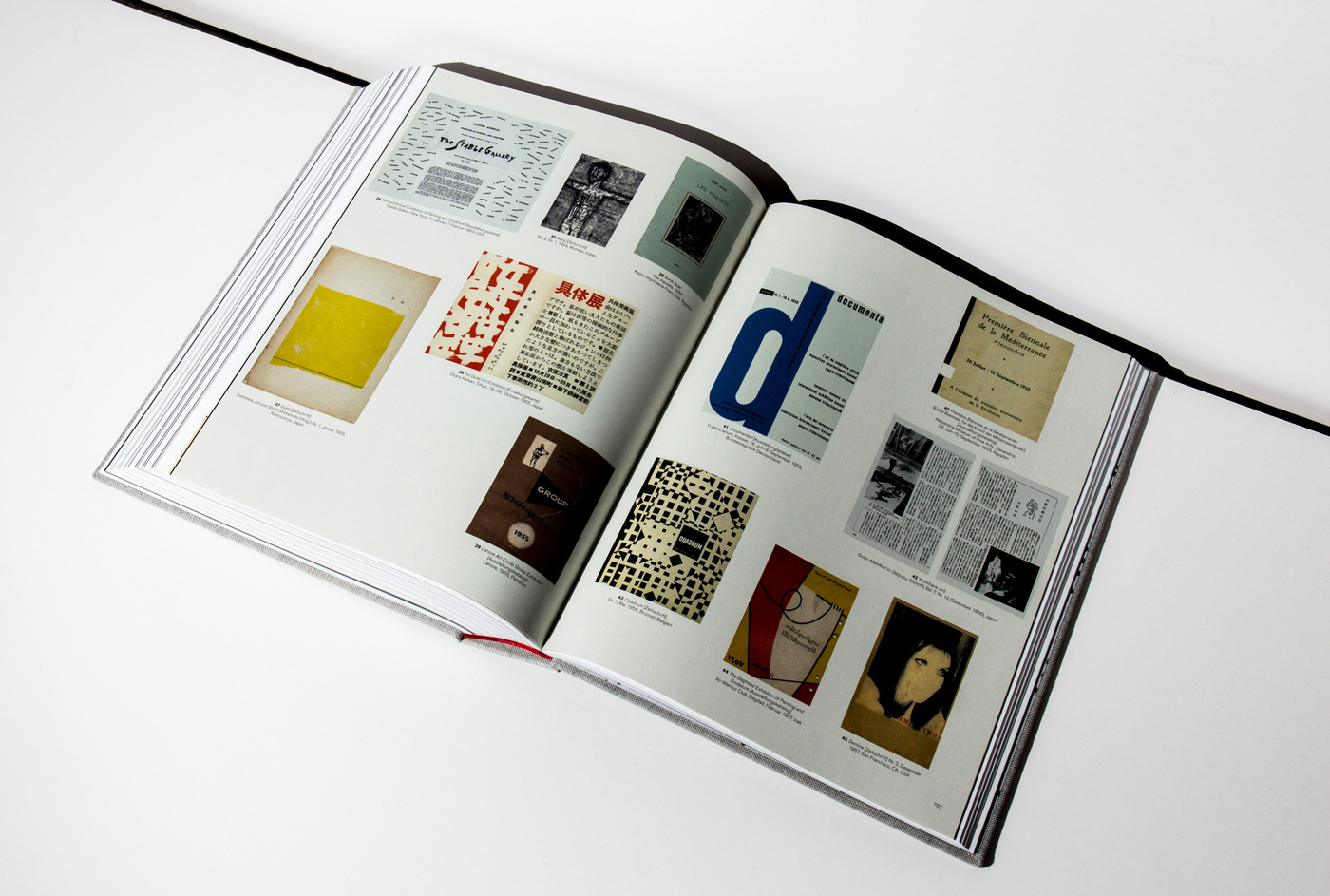

As an in-depth, global study, the exhibition shows painting, sculpture, installation, collage, performance, film, artist books, documents, photography, in total more than 350 works by 218 artists from 65 countries.